Introduction

We are currently at an inflection point. The evidence we have is pointing to a change in direction of Federal Reserve interest rate policy. Earlier this month, both the CPI (Consumer Price Index) and the PPI (Producer Price Incex) showed that inflation was slowing. In fact, the CPI came in below 3% inflation rate for teh first time in nearly 3 1/2 years. Then, this morning, Fed Chairman Powell made a statement from the Federal Reserve Jackson Hole annual economics summit stating that, in essence, the Fed sees inflation under control and that they are ready to start lowering rates.

Because of this, the Fed Fund Futures markets are forecasting a near 100% chance of a September rate cut, with it being split nearly evenly between a forecasted 1/4% and 1/2% cut. Given this, I thought we should discuss inflation and what it means for investors, including our Investment Strategy for client portfolios.

As always, words in green represent links to outside information that you might find interesting.

Understanding Inflation Dynamics, Fed Policy, and its Impact on Financial Markets

Falling inflation marks a shift in the current economic landscape. As inflation rates decrease, the purchasing power of money stabilizes, fostering an environment conducive to economic growth. This decline is crucial, particularly after a period of heightened inflationary pressures that strained both consumers and businesses.

Don’t misunderstand the nuance here: we still have inflation that is increasing, but it is growing a slower pace than previously. Slow growth inflation is the policy of the Federal Reserve that has a 2% target for annual inflation. This is part of what’s called the Federal Reserve Mandate.

The Federal Reserve Mandate, often referred to as the “dual mandate,” was established to guide the central bank in achieving two primary objectives: maximum employment and stable prices. This mandate was formalized through the Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977, which amended the original Federal Reserve Act of 1913. The dual mandate reflects the recognition that both inflation and unemployment are critical to the overall economic health of the country. By striving to keep inflation low and stable, the Federal Reserve helps maintain the purchasing power of the currency, which is essential for economic stability. Simultaneously, by promoting maximum employment, the Fed aims to ensure that as many people as possible are gainfully employed, contributing to economic growth and social stability.

The theory behind the importance of the dual mandate is rooted in macroeconomic principles. Stable prices are crucial because high inflation erodes purchasing power, creates uncertainty in economic decision-making, and can lead to inefficient allocation of resources. On the other hand, high unemployment represents underutilization of the economy’s labor resources, leading to lower overall economic output and potential social unrest. The Federal Reserve’s ability to influence interest rates and money supply, if done right, allows it to moderate economic fluctuations, balancing the goals of full employment and price stability. This dual focus is intended to create a more stable and prosperous economic environment benefitting society as a whole by fostering sustainable growth and minimizing the severity of economic downturns.

BLS Inflation Calculation and Its Evolution

The calculation of inflation has changed over time. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is the arm of the government that calculates inflation. The BLS calculates inflation using the CPI and the PPI, which measures the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. Our focus below is on the CPI whose calculation has undergone significant changes over the years:

Introduction of Hedonic Adjustments (1980s and 1990s):

- Explanation: Hedonic adjustments account for changes in the quality of goods and services. For example, if a new model of a car is more expensive but also has better fuel efficiency, the price increase is partially offset by the improvement in quality.

- Impact: This adjustment tends to lower the reported rate of inflation by reducing the weight of price increases associated with improved products.

- Support: Proponents argue that hedonic adjustments are necessary for accurately reflecting the true cost of living by accounting for quality improvements in products. For example, if a new model of a car is more expensive but offers better fuel efficiency or safety features, the hedonic adjustment would offset some of that price increase. This method ensures that inflation measurements don’t overstate the impact of price changes on consumers, making the data more reflective of actual economic conditions.

- Opposition: Critics, however, argue that hedonic adjustments can obscure the real increases in costs that consumers face. They claim that these adjustments can lead to a systematic understatement of inflation, as they often do not reflect the lived reality of consumers who may not perceive the added value in quality improvements. Some go as far as calling it a “blatant lie” when used to portray the increases in actual costs of living, arguing that it downplays the economic challenges faced by ordinary citizens (Wolf Street).

Substitution Effect (1999):

- Explanation: The BLS introduced a substitution method in 1999, where if the price of one item rises significantly, it is assumed that consumers will switch to a cheaper alternative. This change reflects consumer behavior but can also reduce the reported inflation rate.

- Impact: The substitution effect tends to understate inflation by replacing more expensive items with cheaper alternatives in the CPI basket.

- Support: The introduction of the substitution effect in 1999 was intended to more accurately capture consumer behavior. When prices of certain items rise significantly, consumers often switch to cheaper alternatives. The substitution effect attempts to mirror this shift in spending habits, which can help to avoid overstating inflation by assuming consumers will always choose the most cost-effective options available.

- Opposition: Detractors argue that the substitution effect can lead to an understatement of inflation because it assumes consumers are always able and willing to substitute with lower-cost alternatives. This assumption may not hold true in all cases, particularly for essential goods where there are no suitable substitutes. As a result, the CPI might not fully capture the burden of price increases on consumers, especially in scenarios where there are few or no viable alternatives (FactCheck.org).

Chained CPI (2013):

- Explanation: The Chained CPI takes into account the substitution effect more comprehensively by assuming that consumers are always looking for the least expensive option.

- Impact: This approach typically results in a lower inflation rate than the traditional CPI calculation.

- Support: The Chained CPI, introduced in 2013, expands on the substitution effect by chaining the spending weights used in CPI calculations from month to month. This approach is viewed as a more accurate reflection of changes in consumer behavior over time, leading to a more precise measurement of inflation. Advocates also highlight that Chained CPI can help reduce the federal deficit by slowing the growth of inflation-linked government benefits and tax brackets, as it typically reports a lower inflation rate.

- Opposition: Critics of the Chained CPI point out that, while it may be more precise in a technical sense, it results in lower cost-of-living adjustments for benefits such as Social Security. Over time, this can lead to a significant reduction in the purchasing power of retirees and others who rely on these benefits. The gradual effects of using Chained CPI might appear small initially, but they accumulate over time, potentially leading to a substantial decrease in real income for those on fixed incomes (FactCheck.org).

The evolution of the BLS’s CPI calculation methods reflects a balance between the desire to improve technical accuracy and capturing the real-world economic impact of inflation on consumers. While these changes have enhanced the theoretical precision of inflation measurements, they also face criticism for potentially understating the financial challenges experienced by the public. The debate continues as experts weigh the trade-offs between methodological rigor and practical applicability in measuring inflation.

Headline CPI vs. Core CPI vs. Super Core CPI

Headline CPI:

- Definition: Headline CPI, often referred to simply as the Consumer Price Index (CPI), is a broad measure that tracks the overall change in the price level of a basket of goods and services purchased by urban consumers. This basket includes everything from food and energy to housing, transportation, and medical care.

- Volatility: Because it includes volatile items such as food and energy, headline CPI can fluctuate significantly from month to month due to factors like weather conditions, geopolitical events, or changes in commodity prices.

Core CPI:

- Definition: Core CPI excludes food and energy prices from the CPI calculation. The rationale behind this exclusion is that food and energy prices tend to be highly volatile, and their fluctuations can distort the underlying inflation trend.

- Usage: Core CPI is often used by policymakers, including the Federal Reserve, to gauge underlying inflation trends. By focusing on less volatile components, it provides a clearer picture of sustained inflation pressures in the economy.

- Criticism: While useful for identifying long-term trends, critics argue that excluding food and energy can make Core CPI less relevant for consumers, who still have to pay for these essential items regardless of price volatility.

Super Core CPI:

- Definition: Super Core CPI is an even more specific measure that typically focuses on the price changes in services excluding housing costs, such as healthcare, education, and transportation services. This measure aims to capture inflation in the service sector, which is often seen as a better indicator of persistent inflationary pressures.

- Importance: Super Core CPI is particularly relevant in assessing the impact of wage growth on inflation, as wages are a significant cost in the services sector. It’s closely watched by economists and policymakers when they are concerned about inflation driven by rising labor costs.

- Current Context: Super Core CPI has gained prominence in recent discussions about inflation, particularly as central banks focus on wage-price spirals and inflation in services as key factors in their monetary policy decisions.

Volatility and Relevance to Consumers:

Headline CPI:

- Comprehensive Measure: Headline CPI is the most comprehensive measure of inflation, encompassing all categories of spending. This includes both goods and services, ranging from everyday grocery items to long-term durable goods.

- Direct Consumer Relevance: It is directly relevant to consumers because it includes essential categories such as food and energy. These categories are significant parts of a household’s budget, despite their price volatility.

- Impact on Budgeting: Price changes in these essential items can have immediate and tangible effects on consumer behavior and household budgeting.

Core CPI:

- Reduced Volatility: Core CPI is designed to be less volatile by excluding the often erratic prices of food and energy. This makes it a more stable measure over time.

- Potential Understatement: By omitting these essential goods, Core CPI may understate the actual inflation consumers experience. For instance, while core inflation might appear moderate, sharp increases in food or energy prices can still strain household finances.

- Focus on Stability: This measure aims to provide a clearer picture of underlying inflation trends without the noise of short-term price shocks.

Super Core CPI:

- Service Sector Focus: Super Core CPI narrows down further to focus primarily on the service sector, excluding even broader categories like housing costs.

- Wage-Driven Inflation Insight: It is particularly relevant for understanding inflation trends driven by wage increases. Since wages form a substantial part of service costs, this measure offers insight into persistent inflationary pressures within the economy.

- Policy Implications: Economists and policymakers closely monitor Super Core CPI when they are concerned about inflation stemming from labor costs and service-related expenses. This measure helps in crafting targeted monetary policies aimed at controlling long-term inflation without affecting short-term economic activities drastically.

Policy Implications:

Headline CPI can influence short-term economic decisions, particularly in areas like cost-of-living adjustments and consumer sentiment.

- Cost-of-Living Adjustments (COLAs): Headline CPI is frequently used to adjust wages, pensions, and social security payments to keep up with inflation. This ensures that purchasing power remains relatively constant despite rising prices.

- Consumer Sentiment: Sudden spikes or drops in the Headline CPI can significantly affect how consumers perceive the economy. High inflation may lead to reduced consumer spending and increased savings as individuals brace for higher costs.

- Government Budgeting: Fluctuations in Headline CPI can also impact government budgets, especially those linked to social programs. Accurate predictions of Headline CPI are crucial for efficient fiscal planning.

Core CPI is a critical measure for central banks when setting interest rates because it reflects more stable, underlying inflation trends.

- Monetary Policy Decisions: Central banks prioritize Core CPI as it eliminates the volatility of food and energy prices, offering a clearer view of sustained inflationary trends. This assists in making well-informed decisions regarding interest rate adjustments.

- Inflation Targeting: Central banks often have specific inflation targets. Core CPI helps them gauge whether current monetary policies are effective in maintaining inflation within desired boundaries.

- Long-Term Economic Planning: By focusing on Core CPI, policymakers can design strategies that foster economic stability without overreacting to temporary price shocks.

Super Core CPI is increasingly important for assessing long-term inflation pressures, especially in an economy where services play a dominant role.

- Service Sector Dominance: As economies evolve, services often constitute a larger portion of economic activity. Super Core CPI focuses on this sector by excluding even broader categories such as housing costs, providing a more precise measure of service-related inflation.

- Wage-Driven Inflation Insight: Since wages are a significant component of service costs, Super Core CPI offers valuable insights into how wage increases impact overall inflation. This is particularly relevant in labor-intensive industries where wage changes can directly influence service prices.

- Targeted Monetary Policies: Policymakers rely on Super Core CPI to craft targeted interventions aimed at controlling wage-driven inflation without stifling short-term economic growth. This approach helps balance the need for stable prices with the goal of sustaining healthy economic activity.

By understanding these different measures—Headline CPI, Core CPI, and Super Core CPI—policymakers can better navigate the complex landscape of economic planning and ensure more precise and effective interventions.

PCE Deflator

The Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Deflator is a key measure of inflation used by the Federal Reserve to gauge changes in the price of goods and services consumed by households. It reflects how much prices are rising or falling over time and is considered more comprehensive than the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Unlike the CPI, which measures price changes based on a fixed basket of goods and services, the PCE Deflator accounts for changes in consumer behavior, such as substituting cheaper goods for more expensive ones. This makes the PCE Deflator a more flexible and potentially accurate reflection of actual consumer spending patterns.

The Federal Reserve places significant importance on the PCE Deflator because it provides a broader measure of inflation, including a wider range of expenditures than the CPI. The Fed uses the PCE Deflator to inform its monetary policy decisions, particularly in relation to its 2% inflation target. The preference for the PCE Deflator stems from its ability to better capture the overall inflationary trends in the economy, allowing the Fed to make more informed decisions to achieve its dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment.

Alternative Organizations Calculating Inflation

Several organizations and analysts calculate inflation differently from the BLS. Some of the most notable ones include:

Shadow Government Statistics (ShadowStats):

- Methodology: ShadowStats, founded by economist John Williams, calculates inflation using methodologies that were employed by the BLS before 1980 and 1990. Williams argues that the BLS has systematically altered its methods over the years to understate inflation.

- Differences: ShadowStats excludes adjustments such as hedonic quality adjustments and substitution effects that the BLS currently uses. Instead, it adheres to the older fixed-basket Consumer Price Index (CPI) approach.

- Impact: According to ShadowStats, the inflation rate is significantly higher than the official BLS numbers. For example, if the BLS reports a 3% inflation rate, ShadowStats might calculate it as 7% or higher, based on older methodologies.

The Chapwood Index:

- Methodology: The Chapwood Index measures the cost of living in 50 major U.S. cities by tracking the price changes of 500 items frequently purchased by the average consumer, without any adjustments or modifications.

- Differences: Unlike the BLS, which uses a weighted basket of goods and services, the Chapwood Index simply tracks price changes on a set list of items, claiming this approach reflects the real cost of living increases more accurately.

- Impact: The Chapwood Index often shows inflation rates much higher than the official BLS data, sometimes reporting annual inflation rates of 10% or more, depending on the city.

Comparative Analysis of BLS vs. Alternative Inflation Measures

If we were to apply older and alternative methodologies to today’s inflation, the inflation rate would likely be much higher than the current BLS-reported figures. For example:

- ShadowStats: If we applied the pre-1980 or pre-1990 BLS methods to today’s economy, inflation could be estimated at rates similar to those seen in the 1970s and 1980s, potentially ranging from 7% to 15%, depending on the specifics of the method used.

- Chapwood Index: The Chapwood Index suggests that the real cost of living has been increasing by approximately 10% or more annually in many U.S. cities, which is significantly higher than the BLS-reported inflation rate of around 3-5% in recent years.

These different methods of calculating inflation highlight a significant divergence in the understanding and reporting of inflation’s impact on the economy. The BLS, by incorporating quality adjustments, substitution effects, and the Chained CPI, tends to report lower inflation rates. The PCE Deflator typically reports slightly lower inflation rates than the CPI, due to the differences in methodology. Some economists argue that these two calculations do not fully capture the real cost of living increases faced by consumers and that alternative measures like those from ShadowStats and the Chapwood Index suggest that if older or more straightforward methods were used, today’s inflation would be reported as much higher. They posit that the alternate calculations are reflecting a more pronounced erosion of purchasing power for the average consumer.

Potential Impact of Understated Inflation on Monetary Policy and Economic Stability

If the alternative inflation measures, such as those proposed by ShadowStats and the Chapwood Index, are indeed more accurate reflections of the true cost of living increases faced by consumers, the implications for both monetary policy and economic stability could be significant. The current methodologies used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure, the PCE Deflator, are acknowledged to report lower inflation rates, which might lead policymakers to underestimate the real erosion of purchasing power experienced by households.

In an environment where inflation is understated, the Federal Reserve might adopt a more dovish stance, potentially cutting interest rates or maintaining them at lower levels for longer periods. This approach is designed to stimulate economic activity by making borrowing cheaper, thereby encouraging investment and spending. However, if the actual inflation rate is higher than reported, such rate cuts could exacerbate inflationary pressures, leading to a further decrease in real wages and purchasing power.

Moreover, prolonged periods of low-interest rates in the face of higher-than-reported inflation could distort economic signals, leading to misallocations of capital and increased financial instability. Consumers and businesses might take on excessive debt, believing that borrowing costs will remain low, only to be caught off guard if inflationary pressures force the Fed to tighten monetary policy more aggressively in the future. This could lead to a rapid increase in interest rates, triggering economic shocks and a potential recession. This is clearly something to keep in mind in the process of portrfolio management.

Federal Reserve Policy Tools

The Federal Reserve has multiple tools to respond to falling inflation to stimulate the economy. These tools are designed to encourage spending, investment, and lending, thereby supporting economic growth and preventing deflation. Below is an expanded examination of the potential actions the Fed may take, along with historical examples that illustrate their impact.

1. Lowering Interest Rates

One of the most direct ways the Federal Reserve can respond to declining inflation is by lowering interest rates. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) adjusts the federal funds rate, which is the interest rate at which banks lend to each other overnight. Lowering this rate reduces borrowing costs across the economy, encouraging both consumer spending and business investment.

Specific Impacts:

- Consumer Spending: Lower interest rates make loans and mortgages more affordable, encouraging consumers to borrow and spend more. This can lead to increased demand for goods and services, which helps drive economic growth.

- Business Investment: With cheaper borrowing costs, businesses are more likely to invest in new projects, expand operations, and hire additional workers, further stimulating the economy.

- Debt Servicing: For both households and businesses, lower interest rates reduce the burden of existing debt, freeing up capital that can be redirected toward consumption or investment.

Historical Example: During the global financial crisis of 2008, the Federal Reserve rapidly cut the federal funds rate from 5.25% in September 2007 to nearly zero by December 2008. This aggressive easing was aimed at mitigating the severe downturn in economic activity. The lower rates helped stabilize financial markets, supported consumer spending, and eventually contributed to the recovery.

Less understood and less utilized is the Fed’s lowering of the Discount Rate. Lowering the discount rate, the interest rate at which commercial banks borrow from the Federal Reserve, makes borrowing cheaper for banks, encouraging them to lend more to businesses and consumers. This increase in lending can stimulate economic activity by boosting spending and investment, potentially leading to higher growth. However, if not carefully managed, it can also increase inflationary pressures by driving up demand, which may eventually require the Fed to tighten monetary policy to prevent overheating in the economy.

2. Quantitative Easing (QE)

When traditional interest rate cuts are insufficient to stimulate the economy—especially when rates are already near zero—the Fed may resort to Quantitative Easing (QE). QE involves large-scale purchases of government bonds and other financial assets by the Fed, which injects liquidity directly into the financial system.

Specific Impacts:

- Lower Long-Term Interest Rates: By purchasing long-term securities, the Fed increases their prices, which inversely lowers their yields. This reduction in long-term interest rates encourages borrowing and investment in long-term projects like housing and infrastructure.

- Asset Price Support: QE tends to elevate the prices of a wide range of assets, including stocks and real estate, as investors move their money into riskier assets in search of higher returns. This can create a wealth effect, where increased asset values boost consumer confidence and spending.

- Increased Bank Lending: The liquidity provided by QE enhances the reserves of banks, enabling them to lend more to consumers and businesses, thereby further stimulating economic activity.

Historical Example: The Federal Reserve launched multiple rounds of QE between 2008 and 2014 in response to the financial crisis and its aftermath. The first round (QE1) began in November 2008, with the Fed purchasing $600 billion in mortgage-backed securities. This was followed by QE2 in 2010 and QE3 in 2012. These programs helped stabilize financial markets, supported economic recovery, and kept long-term interest rates low, even as the economy faced significant challenges.

The positive impact on stock prices was undeniable as massive liquidity flowed from the government into investors hands. The question that I have – which is really for another blog post – what are the long-term repercussions of this drastic step.

3. Forward Guidance

Forward guidance is a communication tool used by the Federal Reserve to signal its future policy intentions to the markets. By providing clarity on the likely path of interest rates and other policy measures, the Fed can influence market expectations and stabilize financial markets – much like we saw in today’s press conference.

Specific Impacts:

- Market Stability: Clear and consistent forward guidance helps reduce uncertainty, which can stabilize financial markets and encourage investment.

- Anchoring Expectations: By signaling a commitment to low interest rates for an extended period, the Fed can anchor inflation expectations, ensuring that consumers and businesses do not defer spending or investment out of fear of future deflation.

Historical Example: In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve used forward guidance extensively. Starting in 2011, the Fed explicitly stated that it expected to keep the federal funds rate near zero for an extended period, initially until mid-2013, later extending this to 2015. This forward guidance helped shape market expectations, contributing to economic stabilization during a period of uncertainty.

4. Adjusting Reserve Requirements

Reserve requirements refer to the amount of funds that banks must hold in reserve and not lend out. By lowering these requirements, the Fed can increase the amount of money available for lending and investment.

Specific Impacts:

- Increased Lending Capacity: Lower reserve requirements mean that banks have more funds available to lend, which can lead to an increase in credit availability for consumers and businesses.

- Enhanced Economic Activity: By boosting the availability of credit, the Fed can stimulate economic activity, especially during periods of low inflation or economic downturn.

Historical Example: While changes in reserve requirements are less commonly used in modern monetary policy compared to interest rate adjustments and QE, they have been employed during critical periods. For example, during the Great Depression, the Federal Reserve reduced reserve requirements in the early 1930s to encourage lending and counter the severe contraction in the money supply.

Investor Opportunities in a Low-Inflation, Accommodative Fed Policy Environment

The combination of falling inflation and a supportive Federal Reserve policy creates a unique set of opportunities for investors across different asset classes. By understanding how these dynamics affect various markets, investors can position their portfolios to capitalize on the prevailing economic conditions.

1. Fixed-Income Assets

In an environment of falling inflation and accommodative monetary policy, fixed-income assets, particularly bonds, often become more attractive for several reasons:

a. Rising Bond Prices: As the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates and engages in policies like Quantitative Easing (QE), bond yields typically fall. Since bond prices move inversely to yields, this can lead to an increase in bond prices, offering capital gains opportunities for investors. For those who hold existing bonds, the appreciation in bond prices can provide an attractive exit point.

b. Lower Risk of Inflation Erosion: With inflation expectations low, the real returns on bonds are less likely to be eroded by rising prices. This makes bonds a safer store of value, especially government and high-quality corporate bonds, which are less risky compared to equities.

c. Income Stability: For income-focused investors, the stability of returns provided by bonds becomes more appealing, particularly in a low-interest-rate environment where alternative income-generating investments might offer less attractive risk-adjusted returns.

Historical Example: The 40-year bull market in bonds, which began after the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker ended its aggressive tightening in the early 1980s, serves as a prime example of how falling inflation and accommodative monetary policy can benefit fixed-income investors. After Volcker successfully curbed the high inflation of the 1970s through extremely high interest rates, inflation expectations began to stabilize. This allowed the Fed to gradually lower interest rates from their peak in 1981, leading to a steady decline in bond yields over the following decades. As yields fell, bond prices rose, resulting in significant capital gains for bondholders. This period saw U.S. Treasuries and other fixed-income assets deliver strong returns, making bonds one of the best-performing asset classes during this era.

2. Equities

Equity markets can also benefit from the interplay between falling inflation and accommodative Fed policy. Several factors contribute to the attractiveness of stocks in such an environment:

a. Lower Borrowing Costs: When the Fed lowers interest rates, it reduces the cost of borrowing for companies. This can boost corporate profits by lowering the expense of debt servicing and making it cheaper for companies to finance expansion, mergers and acquisitions, and other growth initiatives. Increased profitability often translates into higher stock prices.

b. Enhanced Valuations: Lower interest rates typically result in lower discount rates used in equity valuation models. As a result, the present value of future earnings and cash flows increases, which can lead to higher stock valuations. This dynamic is particularly favorable for growth stocks, which derive much of their value from expected future earnings.

c. Increased Consumer Spending: With lower borrowing costs, consumers are more likely to spend, especially on big-ticket items like homes and cars. This increase in consumer demand can drive higher revenues for companies, further supporting equity markets.

d. Sector Opportunities: Certain sectors tend to perform particularly well in low-interest-rate environments. For example:

- Technology and Growth Stocks: These sectors benefit from the lower cost of capital, which supports their high-growth business models.

- Real Estate: Real estate investment trusts (REITs) often perform well as lower interest rates reduce financing costs and boost property values.

- Consumer Discretionary: Increased consumer spending can benefit companies in sectors such as retail, automotive, and luxury goods.

- Utilities: As a bond proxy, utilities tend to increase in value as interest rates decrease.

- Dividend Aristocrats: Dividend Aristocrats are a special category of companies that have paid and raised their dividend payouts for at least 25 consecutive years – some well over 100 years.

Historical Example: The post-2008 financial crisis period saw a significant bull market in equities, driven by the Fed’s zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and multiple rounds of QE. Tech stocks, in particular, saw massive gains, with the Nasdaq Composite index rising from around 1,500 points in 2009 to over 5,000 points by 2015. The lower borrowing costs and abundant liquidity created by Fed policies were key drivers of this surge in stock prices.

3. Real Estate

Real estate can also become a lucrative investment in a low-inflation environment with accommodative Fed policy. Lower interest rates make mortgage financing more affordable, which can lead to increased demand for housing and commercial properties. This demand can drive up property values and rental income, making real estate an attractive asset class for both income and capital appreciation.

a. Residential Real Estate: Lower mortgage rates increase affordability for homebuyers, often leading to a rise in housing demand. This demand can push up home prices, benefiting homeowners and real estate investors alike.

b. Commercial Real Estate: Lower borrowing costs also benefit commercial real estate developers and investors. The reduced cost of capital makes it easier to finance new projects, leading to potential gains in property values and rental yields. Sectors such as office spaces, retail properties, and industrial real estate can see significant investment returns in this environment.

Historical Example: The real estate market recovery after the 2008 crisis, particularly in the residential sector, was partly driven by the Fed’s low-interest-rate policies. Housing markets in cities like San Francisco, New York, and Los Angeles saw significant price appreciation as buyers took advantage of historically low mortgage rates.

4. Commodities and Precious Metals

While lower inflation generally dampens the appeal of commodities, precious metals like gold can still thrive in an environment of falling inflation and accommodative monetary policy. This is because gold is often seen as a hedge against both inflation and economic uncertainty.

a. Safe-Haven Appeal: Gold and other precious metals are considered safe-haven assets. In times of economic uncertainty or when real interest rates are low (nominal interest rates minus inflation), the opportunity cost of holding non-yielding assets like gold decreases, making them more attractive.

b. Currency Depreciation: If the Fed’s accommodative policies lead to a depreciation of the U.S. dollar, gold, which is priced in dollars, typically becomes more valuable. Investors often flock to gold as a store of value when they anticipate currency depreciation.

Historical Example: Gold prices surged during the years following the 2008 financial crisis, reaching an all-time high of over $1,900 per ounce in 2011. This was driven by the Fed’s aggressive monetary easing and the associated concerns over currency depreciation and global economic stability.

The Impending Rate Cuts: Implications for Investors

Anticipated Fed Rate Cuts in September

After this month’s inflation numbers hit plus today’s Forward Guidance, Fed Fund Futures Markets have gone full tilt boogie. Below, we are focusing on how the near 100% chance of a rate cut impacts portfolio management. The anticipated reduction in the Fed Funds Rate suggests a strategic shift toward more accommodative monetary policy and an intention to stimulate the economy, thereby making certain investments and investment strategies more attractive.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Bond Yields: Understanding the Yield Curve

The relationship between short-term and long-term yields, often depicted through the yield curve, provides critical insights into market expectations and economic health.

- Short-Term Rates: When the Federal Reserve lowers short-term rates, it directly impacts yields on short-term bonds. These yields generally decline in tandem with rate cuts.

- Long-Term Bonds: Conversely, long-term bond yields are influenced not only by current monetary policy but also by longer-term inflation expectations and economic growth projections.

Yield Curve Dynamics

The yield curve is a widely used predictor of future economic growth due to its ability to reflect investor expectations about the economy. Typically, a normal yield curve slopes upward, indicating that longer-term bonds have higher yields than shorter-term ones, reflecting expectations of future economic expansion and higher inflation.

However, when the yield curve inverts—meaning short-term rates exceed long-term rates—it suggests that investors expect slower growth or even a recession. This inversion occurs because investors anticipate the need for future rate cuts by central banks to combat economic downturns, leading them to seek the safety of long-term bonds, thus pushing their yields lower. Historically, an inverted yield curve has been a reliable indicator of impending recessions, as it reflects a pessimistic economic outlook among investors and a potential tightening of credit conditions, which can dampen future growth.

The yield curve shapes signaling different economic outlooks:

- Normal Yield Curve: Typically upward sloping, indicating that long-term bonds have higher yields than short-term ones due to perceived higher risk over time.

- Inverted Yield Curve: Occurs when short-term yields exceed long-term yields, often viewed as a predictor of economic recession. In fact, we are currently in the longest inverted yield curve in history, time-wise.

- Flat Yield Curve: Signifies minimal difference between short- and long-term yields, suggesting uncertainty about future economic conditions.

Lowering short-term rates can steepen the yield curve if long-term rates remain stable or rise slightly due to improved growth expectations. Investors might interpret a steepening yield curve as a positive signal for future economic expansion.

Inflation’s Impact on Bond Markets

1. Bond Yields and Inflation Expectations

Lower inflation has a direct impact on bond yields. Bond yields are the return an investor expects to receive from holding a bond, and they are closely tied to inflation expectations. When inflation is low, the purchasing power of future cash flows from bonds is less likely to erode, meaning investors do not demand as high a yield to compensate for this risk. Historically, periods of declining inflation have been associated with falling bond yields.

Historical Example: The United States in the 1980s serves as a classic example. Under Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, aggressive monetary tightening policies were implemented to combat the rampant inflation of the late 1970s. As inflation was brought under control, bond yields, which had been extremely high, began to decline. The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond peaked at over 15% in 1981 but steadily fell as inflation expectations were tamed, dropping to around 7% by the end of the decade.

2. Bond Prices and Yield Inverse Relationship

There is an inverse relationship between bond yields and bond prices. As yields drop due to lower inflation expectations, existing bonds with higher coupon rates become more attractive, leading to an increase in their market price. This price appreciation can create significant opportunities for investors, particularly in an environment where yields are consistently falling.

Historical Example: During the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, central banks around the world, including the Federal Reserve, slashed interest rates to near zero to stimulate the economy. As a result, bond yields plummeted, leading to a surge in bond prices. Investors who held long-term government bonds during this period experienced substantial price gains as yields on the 10-year U.S. Treasury fell from around 4% before the crisis to below 2% by mid-2012.

Historical Example: An extreme example of falling bond yields leading to an increase in bond prices can be observed during the 40-year bond bull market that began in the early 1980s. This period was characterized by a consistent decline in interest rates following the peak of inflation and interest rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As interest rates fell, bond yields decreased, which in turn caused bond prices to rise significantly.

For example, consider a long-term U.S. Treasury bond with a 30-year maturity bought in 1990, when yields were around 8%. As the Federal Reserve continued to lower interest rates throughout the 1990s and 2000s, yields on long-term bonds declined, falling to around 3% by 2015. This significant drop in yields would have resulted in a substantial increase in the bond’s price.

To illustrate this with a hypothetical return, assume an investor purchased a 30-year Treasury bond with an 8% coupon rate at par ($1,000) in 1990. By 2015, the bond’s yield dropped to around 3%, meaning the bond’s price would have increased as the fixed coupon payments became more valuable in a lower interest rate environment. Using a bond price calculation, the bond would have appreciated to approximately $2,000 or more while you collected $500 in interest income, resulting in a total return of over 250% when combining both capital gains and interest income over the 25-year period.

This is a very good return for a credit-risk-free investment, although it doesn’t compare to an investment in the stock market over the same period of time. For example, if you had purchased $1,000 of Johnson & Johnson stock on the first trading day of 1990 and sold it on the last trading day of 2015, you would have had $18,895 in Capital Gains and collected $8,325 in Dividends, for a total return on your original $1,000 investment of $27,220 or 2,725% over the same period. Considerably more than the 250% fixed income alternative, but it did include bear markets and market crashes along the way where you could have lost money or lst a significant part of your gains had you panicked and sold irrationally.

Portfolios have a place for both slow and steady fixed income as well as riskier but potentially more rewarding equity investments – it just matters in what proportion and how much risk you are willing to assume.

3. Additional Factors Influencing Bond Prices and Yields

While inflation and interest rates are critical drivers of bond yields and prices, they are not the only factors at play. Several other elements can influence bond markets, sometimes complicating the straightforward relationship between inflation and bond performance.

a. Credit Risk: For corporate bonds and bonds issued by less creditworthy governments, credit risk (the risk of default) plays a significant role in determining yields. Even in a low-inflation environment, if a bond issuer’s creditworthiness deteriorates, investors will demand higher yields as compensation for the increased risk, leading to a drop in bond prices.

Historical Example: The European sovereign debt crisis in the early 2010s highlighted the importance of credit risk. Despite low inflation in the Eurozone, countries like Greece and Italy saw their bond yields soar due to concerns over their ability to repay debt. Greek bond yields, for instance, spiked to over 35% in 2012, even as the European Central Bank maintained low-interest rates.

b. Supply and Demand Dynamics: The supply of and demand for bonds can also significantly influence bond prices and yields. For instance, large-scale bond purchases by central banks (known as quantitative easing) can drive up bond prices and lower yields, independent of inflation trends.

Historical Example: The Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE) programs following the 2008 financial crisis provide a clear example. By purchasing large quantities of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities, the Fed drove down yields across the board. Even as inflation remained low, the sheer demand from the Fed kept bond prices high and yields suppressed.

c. Global Economic Conditions: Global economic events and uncertainties, such as geopolitical tensions, can lead investors to seek safe-haven assets like US government bonds, driving up prices and lowering yields. This is often seen during periods of economic or political instability. This is colloquially called a “Flight To Safety.”

Historical Example: In response to the Brexit referendum in 2016, there was a significant flight to safety, with investors flocking to U.S. Treasuries. The uncertainty surrounding the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union led to a sharp decline in U.S. bond yields, even though domestic inflation expectations had not changed dramatically. The 10-year Treasury yield dropped to a then-historic low of around 1.36% in July 2016.

Economic Changes Bring Stock Market Opportunities

Bond Market Factors and Stock Market Performance

The bond market and the stock market are deeply interconnected, and changes in the bond market can significantly impact the performance of the stock market. Here’s how:

Economic Indicators and Sentiment

Although falling interest rates act as a stimulus to stock prices in the short-term, medium term they can be an indication of trouble if economic growth does not pick up quickly enough for investor appetites.

The bond market often reacts quickly to changes in economic indicators such as GDP growth, unemployment rates, and inflation data. A strong bond market performance, characterized by falling yields, can indicate investor expectations of slower economic growth or potential economic downturns. This sentiment can spill over into the stock market, leading to increased volatility or declining stock prices as investors become more cautious.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, for example, bond yields fell sharply as investors flocked to the relative safety of government bonds, signaling fears of a severe economic downturn. This contributed to sharp declines in stock markets worldwide as investors reassessed the economic outlook.

Risk Appetite and Market Sentiment

The bond market is also a reflection of investors’ risk appetite. When investors are risk-averse, they tend to buy bonds, particularly government bonds, which are considered safer investments. This flight to safety can cause bond prices to rise and yields to fall, while stock prices may decline as investors move away from riskier assets like equities. Conversely, when investors are more willing to take on risk, a shift in sentiment occurs and they may sell bonds in favor of stocks, pushing stock prices higher.

The Shift in Sentiment

The shift in investor preference often redirects capital into the stock market in spite of the capital gain opportunity of increasing bond prices. Growth sectors, particularly technology, benefit from this influx of capital due to their potential for substantial revaluation and earnings growth.

Anticipated Federal Reserve rate cuts are expected to push this trend along. Lower interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing for companies, facilitating investment in innovation and expansion. Industries that rely on borrowing to fund cyclical operations or scale growth, stand to gain substantially. Additionally, as interest rates lower, investors desire for margin leverage increases as the cost to borrow funds to buy stocks decreases providing an additional source of capital to fuel a stock market up-trend.

Fed Policy and a Soft Landing

With the announcement of impending rate cuts, the Federal Reserve is trying to achieve a soft landing as opposed a recession that results if they keep monetary policy too restrictive for too long. In the new conference we noted earlier, the Fed believes it has achieved a soft landing and that it is time to loosen the currently tight monetary policy thereby avoiding a recession.

A “soft landing” refers to a scenario in which a central bank, like the Federal Reserve, successfully slows down an overheated economy to curb inflation without causing a significant increase in unemployment or triggering a recession. Achieving a soft landing is challenging because it requires careful adjustments to monetary policy, typically through interest rate hikes, to cool economic growth just enough to keep inflation in check without stifling economic activity altogether.

How a Soft Landing Relates to a Goldilocks Economy

A Goldilocks economy is an ideal state where economic conditions are “just right”—characterized by steady growth, low inflation, and low unemployment. This environment is conducive to stable and sustained economic expansion without the extremes of overheating or contraction.

A soft landing is essentially an attempt to maintain or restore a Goldilocks economy. When an economy is growing too quickly, it risks entering a phase of high inflation (like we have just experienced), which can disrupt the balance that defines a Goldilocks economy. To prevent this, central banks may implement tighter monetary policies, such as raising interest rates, to slow down economic growth. The goal of these measures is to cool down inflationary pressures without tipping the economy into a recession—a scenario that would disrupt the balance of growth, employment, and inflation.

The Challenges and Risks of Fed Policy Changes

Achieving a soft landing is notoriously difficult because it involves precise timing and a deep understanding of economic signals. If the central bank acts too aggressively, it could push the economy into a recession, resulting in a “hard landing.” Conversely, if the measures are too mild, the economy might continue to overheat, leading to runaway inflation.

The success of a soft landing hinges on the central bank’s ability to strike the right balance—akin to maintaining the conditions of a Goldilocks economy. Both scenarios require a delicate equilibrium where economic growth is sustainable, inflation is kept in check, and employment levels remain healthy. When a soft landing is successful, it can preserve or create the conditions for a Goldilocks economy, offering a stable environment for businesses and investors.

So far in the current economic cycle, it looks like the Fed is on the way to a soft landing. If they do achieve it – and it will be 9 to 18 months before we know if the anticipated rate cuts keep us from recession – then we are set up for the Goldilocks economy desired by investors. However, since we have quite a bit of time before we know if the change in policy will be successful, we need to understand the implications of either scenario. Here are two examples of changes in Fed policy leading to wildly different outcomes.

Historic Example: The Goldilocks Economy of the Mid-to-Late 1990s: The mid-to-late 1990s in the United States is often cited as a classic example of a Goldilocks economy—a period where economic conditions were “just right.” During this time, the U.S. economy experienced robust growth driven by technological innovation, particularly in the information technology sector, which fueled productivity gains and corporate profits. The unemployment rate fell steadily, reaching a low of around 4% by the end of the decade, signaling a strong labor market where jobs were plentiful.

Despite this economic expansion, inflation remained remarkably stable, hovering around 2% annually, well within the Federal Reserve’s target range. The combination of strong economic growth, low unemployment, and stable inflation created a favorable environment for businesses and consumers alike, allowing for sustained economic prosperity without the typical overheating that could lead to rising prices. The Federal Reserve, under Chairman Alan Greenspan, successfully managed monetary policy to support this balance, contributing to what many regard as an ideal economic period that has become known as The Great Moderation.

Historic Example: The Stagflation of the Late 1970s

In stark contrast, the late 1970s in the United States is an example of a period where a Goldilocks economy was not achieved. Instead, the country faced stagflation, a challenging economic condition characterized by high inflation, stagnating economic growth, and rising unemployment—an unusual combination that defied traditional economic models. During this time, inflation rates soared, reaching double digits due in part to supply shocks like the oil crisis, which drove up prices for energy and goods across the board. At the same time, economic growth stalled, with GDP growth rates slowing considerably, leading to high unemployment and a general sense of economic malaise.

The Federal Reserve, under Chairman Paul Volcker, eventually took aggressive action by sharply raising interest rates to combat inflation, which, while necessary to bring prices under control, initially exacerbated the economic slowdown. This period is often referenced as a cautionary tale in economic policy, illustrating the difficulties and complexities of managing an economy where inflation and unemployment are both rising simultaneously, far from the balanced conditions of a Goldilocks economy.

Understanding these dynamics provides a framework for navigating long-term investment decisions. Balancing risk with opportunity requires a nuanced approach and adopting the right investment strategy for the specific economic circumstance.

Asset Allocation in a Falling Interest Rate Environment

Asset allocation is a critical component of successful portfolio management, especially in a falling interest rate environment. As interest rates decline, the dynamics of different asset classes shift, necessitating a strategic reassessment of how capital is distributed among them. The performance of various asset classes, such as equities, bonds, and real estate, can diverge significantly depending on the interest rate landscape, making it essential for investors to adjust their strategies accordingly.

In a falling interest rate environment, bonds typically become less attractive as their yields decrease even though they do experience some level of capital gains. This often pushes investors to seek higher returns in equities or other asset classes that can provide cash flow returns in excess of bond interest earned. By overweighting the Equities asset class in your allocation, you are accepting both increased risk and increased potential for return. You must be able to withstand the additional volatility in your portfolio before you make such a change.

You have to remember that not all equities perform equally well when interest rates fall. The key to successful portfolio management lies in understanding the sector-specific implications of lower rates and how different equity types react to falling rates.

Sector-Specific Implications of Lower Rates on Investment Strategies

Effects on Banks’ Profitability

Lower interest rates have a nuanced impact on different sectors. For banks, reduced rates can compress net interest margins—the difference between the interest income generated from lending activities and the interest paid out on deposits. This compression poses challenges for profitability within the financial sector. Banks may struggle to maintain earnings growth if they cannot offset lower margins with increased lending volumes or fee-based services. One thing we know for sure, loans reprice downward faster than deposits as borrowers want to refinance at lower rates but depositors want to keep their higher rates for as long as possible.

Performance of Defensive Sectors

Conversely, defensive sectors like utilities and real estate tend to perform well in low-rate environments. These sectors usually offer stable dividends and are less sensitive to economic cycles, making them attractive to risk-averse investors during periods of economic uncertainty.

Utilities benefit from predictable cash flows and high capital requirements for infrastructure projects, which become more manageable with cheaper borrowing costs.

Real estate investments also thrive under lower interest rates. Reduced borrowing costs make financing property acquisitions more affordable, potentially leading to an increase in property values and rental income. Real estate investment trusts (REITs) often see enhanced performance as a result.

Plus, both asset types typically have high dividend yields which investors value more in a lower rate environment where their interest income is shrinking but their dividends can generally see consistent increases if they choose the right investment.

Enhanced Appeal of Dividend Aristocrat Stocks and High Tech Companies in a Falling Interest Rate and Inflation Environment

In an environment of falling interest rates and declining inflation, the distinction between long-duration and short-duration stocks becomes critical for investors.

Long-duration stocks, such as growth-oriented technology companies that typically pay little or no dividends, derive much of their value from future earnings potential. These stocks are highly sensitive to interest rate changes because their future cash flows are discounted at a lower rate when interest rates decline, leading to higher present valuations. This makes them particularly attractive during periods of rate cuts.

In addition to valuation, their earnings stream also see benefits of lower interest rates. However, it is not due to falling interest rates on their corporate debt since technology companies generally have low leverage. Instead, it’s the lower borrowing costs of their customers that enhance those customers’ ability to invest in cutting-edge technologies at cheaper financing costs. This results in increased revenue growth for technology companies upon which the lower discount rates are applied.

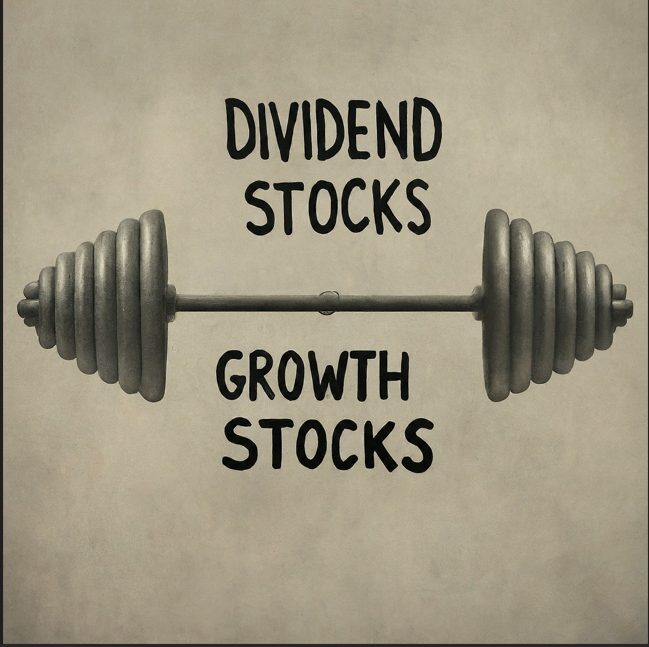

In contrast, short-duration stocks, including Dividend Aristocrats, pay consistent and growing dividends, providing more immediate returns to investors. These stocks are less dependent on future earnings and are generally considered safer in volatile markets. As interest rates fall, the income from bonds and other fixed-income securities decreases, making the steady and growing dividends from short-duration stocks more appealing to income-seeking investors.

Dividend Aristocrats, which are typically found in established, financially stable companies with a long history of increasing dividends, offer a reliable source of income that becomes even more valuable when inflation is low and interest rates are falling. By investing in stocks that consistently raise their payouts – many times much faster than inflation – the companies are enhancing the real returns for investors well beyond what they can get in bonds. Dividend Aristocrats stand out in this scenario because they combine the benefits of regular, growing income with the possibility of price appreciation as lower interest rates generally support higher stock valuations.

Moreover, the companies behind Dividend Aristocrat stocks often belong to defensive sectors such as consumer staples, healthcare, and utilities. These sectors tend to be less sensitive to economic cycles, offering additional stability to investors during periods of economic uncertainty or market volatility. This stability is particularly valuable when economic conditions are unpredictable, as it provides a buffer against market fluctuations.

In contrast, while long-duration growth stocks may see significant price appreciation in a falling interest rate environment, they do not provide the same level of immediate income as short-duration stocks. This can make them less attractive to investors who prioritize regular income or who want to avoid volatility, especially in a low-yield environment.

Investors should consider the different roles that long-duration and short-duration stocks play within a diversified portfolio. While long-duration stocks offer significant growth potential, short-duration stocks like Dividend Aristocrats provide a balanced approach, combining income generation and manageable volatility with the potential for capital appreciation.

Adopting the Barbell Investment Strategy: Balancing Growth and Stability

We are in the process of transitioning portfolios to a Barbell Strategy since it creates a balanced portfolio that leverages falling interest rates and lower inflation.

The barbell investment strategy offers a strategic approach for balancing growth potential with income stability. This strategy involves allocating investment capital to both long-duration and short-duration stocks to create a portfolio that capitalizes on the strengths of both asset types, while under weighting companies, like banks, where falling interest rates present a difficult operating environment.

As discussed earlier:

- Growth-oriented companies (e.g., technology stocks) represent long-duration stocks which typically reinvest earnings back into the business rather than paying dividends, offer substantial future growth potential. Their valuations benefit significantly from lower interest rates, as the discounted value of their future earnings increases. Additionally, with their customers facing reduced borrowing costs, these companies often see an uptick in sales and earnings.

- Dividend Aristocrats provide immediate income through consistent and growing dividends, offering a counterbalance to the more volatile and speculative nature of growth stocks.They become more attractive as the relative appeal of their stable income increases, especially when bond yields are low.

In the recent market pull-back due to the Tokyo stock market flash crash, we purchased two industrial REITS with strong tenants in long-term leases and two utilities that service the exponentially growing cloud farm areas of the country. All four pay strong and growing dividends plus have catalysts for earnings growth.

Additionally, we added to AI positions that sold off during the pullback that have a long, if volatile, runway ahead, and reduced exposure to banks in portfolios that still had it.

In coming weeks, we will continue to add Dividend Aristocrat exposure, particularly those we rank as High Performing companies with a positive technical picture. Our Technology Sector exposure is already pretty solid, but if any of the companies we own disappoint, we will likely swap into alternative growth stocks as need be unless we view the a resulting price correction as temporary and a buying opportunity.

Below is a partial list of companies that fit the Dividend Aristocrat purchase criteria above if you want to put any of them on your watch list – note that in the Dividend Aristocrat column, the numbers in parentheses indicate the number of years in a row that the company has raised its dividend. These are not recommendations to buy – do your own due diligence before you buy any stock for your portfolio. For me, this would be just a starting point for further review and analysis to determine if the risk and potential return characteristics fit my portfolio strategy.

Thanks for reading the blog!

Mark